This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our disclosure policy.

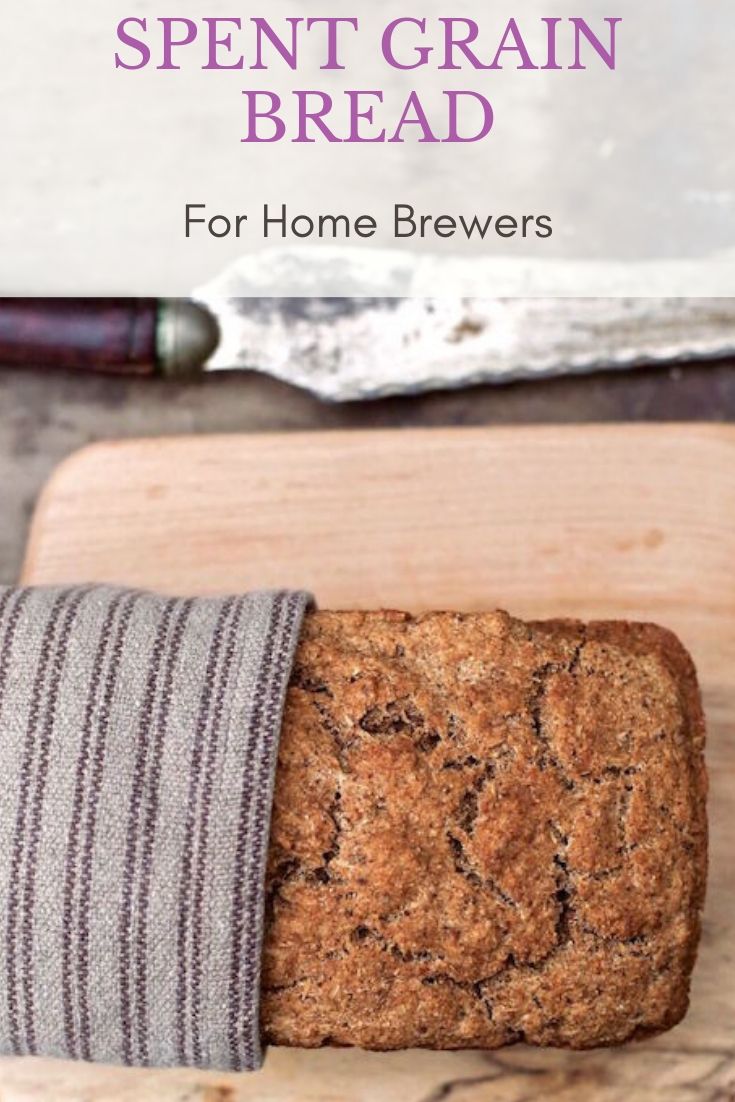

Homebrewing is a really spectacular way to make a unique homemade beer, while saving money at the same time. Once the brew is finished, all that malted barley has one more gift to give ~ Spent Grain Bread.

I’ll admit it, we make a pretty excessive amount of homebrew every year. I want to ferment just about everything I can get my hands on, and there’s nothing like an oak aged double IPA at the end of a long day.

In the past, we’ve found ways to use spent grain mostly by feeding it to our animals. Pigs love brewers grain, and our flock of ducks would battle over it. These days though, we’re mostly herding around toddlers and out homestead animals are down to a small flock of chickens and one geriatric cat.

Sure, we could easily just compost spent grain, but it seems a shame. There’s still so much nutrition left, even if the malty goodness has already been brewed into homemade beer.

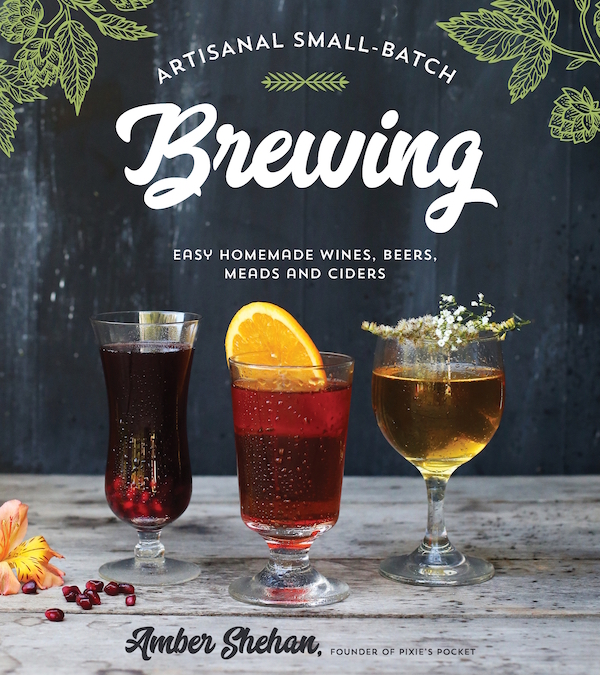

When my friend Amber sent me a copy of her new book, Artisan Small Batch Brewing, I was so excited to find it included plenty of spent grain recipes.

The book includes recipes for making spent grain flour, herbed spent grain crackers, spent grain granola and this spent grain beer bread.

This recipe is really adaptable and works well with added herbs like oregano or thyme. Try grating a bit of hard cheese into the dough, or adding in dried fruit.

There are so many variations, not including all the different flavors from the actual spent grains. This spent grain bread recipe includes beer as well, which means there are even more options for flavor adaptations. As you can imagine a stout will taste a lot different in this bread than an IPA.

Spent Grain Bread

Ingredients

- 3 tbsp 45 g sugar, plus more to dust the pan

- 1½ cups 180 g spent-grain flour (page 148)

- 1½ cups 180 g all-purpose flour

- 1½ tsp 9 g sea salt

- 1 tbsp 11 g baking powder

- 1½ cups 360 ml beer

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C) and grease a loaf pan. If desired, sprinkle a little sugar into the greased pan to give your bread a crisp, sugary crust.

- In a large bowl, mix the spent-grain flour, all-purpose flour, salt, sugar and baking powder. Make a well in the center of the dry ingredients and slowly pour in the beer. Stir well until all of the elements are moist and well distributed.

- Pour the batter into the pan and bake for 45 to 60 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean.

- Remove the bread from the oven and transfer it to a wire rack when the pan is cool enough to handle. Cool the bread completely before slicing.

Notes

More Bread Recipes

Looking for more bread recipes? Read on…

Made a few small changes to the recipe. I used 3 tbsp of honey instead of sugar, used organic bread flour instead of AP flour and used double acting baking powder. I used a local brewery’s IPA for the beer. The result was a moist bread with a strong, slightly bitter flavor. The bread raised well and had a tender texture. I thoroughly enjoyed it. It paired really well with a peach-ginger fruit spread. I will definitely make it again. Very quick and easy to put together!

I hate spent grain flour, seems so wastful to dry it in the oven, especially during warm months when I do most of my brewing.

I prefer to use it fresh, just run it through the food processor for a few minutes to turn it to paste. Not as fine texture as flour but the energy savings is worth it to me.

I usually use it yeast risen bread, but I’m excited to try this quick bread!

Thanks for the idea, Chris! I’ll have to try it as a paste this summer.

Yes this is the spent grain recipe I have been looking for! I have tried cookies so far with brewing grains but I can’t wait to try using my spent grain flour and homebrewed beer to make bread. Thanks!

I’ve been wanting to make spent bread since I first tasted it. Can you tell me a source to get the spent grain from? I would be so grateful.♥️

We do a lot of homebrewing, so I have my fair share on hand. You could try asking around at any local breweries!

Hi, Where can I buy Spent Flour

You can check online, but for the most part, spent grain is a byproduct of homebrewing.

I homebrew and get plenty of Spent Grain but it is moist and grainy, not what I would call flour, but what is Spent Grain Flour? Have you dried it and ground it?

Yes, exactly. You would want to dehydrate and mill your spent grains into flour.